Yanerys lived in the Dominican Republic until she was 10, when she emigrated to the U.S. Her mom crossed into Puerto Rico when she was four months old, and they never met until Yanerys came to join her in New York.

(c) Yanerys

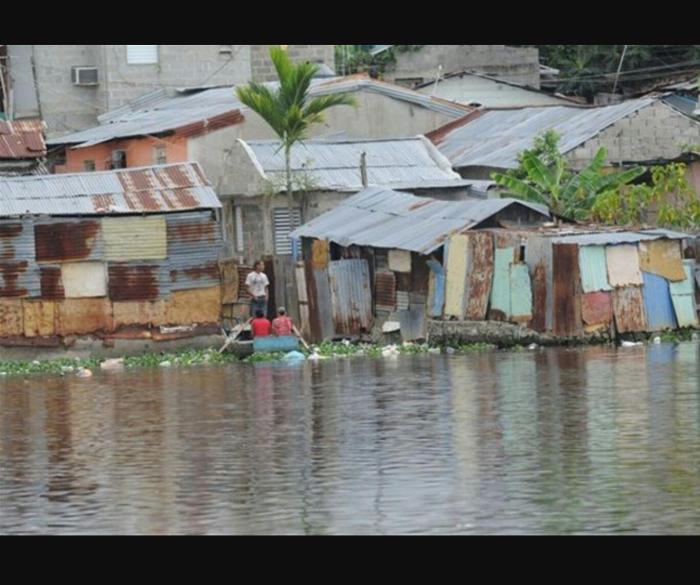

Life in the Dominican Republic is hard, or it was where I grew up. I was born in the Capitol. There’s this section where the river kind of starts, and the garbage ends, and that’s where I lived, in the slums. I didn’t know what hot water was, what toilet paper was. You know that scene in “Slumdog Millionaire,” where he falls in? I never fell all the way in, but…yeah, it was like that.

We had one deodorant for the whole family, and there were 30 of us living in this one-bedroom aluminum house. Aluminum was good, because it was cheap, and it didn’t soak up the rain like wood does.

There was no education. I didn’t know how to read or write. I tried going to school one time, at a neighbor’s house. She was teaching some of the kids. But she got frustrated with me because I don’t know, I wasn’t learning my abc’s fast enough or something, and she told me to hold out my hands so that she could hit them with a ruler. I said no, so she slapped me across the face, so hard. I never went back.

The hitting was normal, though. Getting a slap or a punch is just…that’s just the way it was. It was expected. But I was getting enough of it from my aunts and the other people in my house, so I decided I would help my older sisters, Rosemary and Amnerys. Because we were the youngest generation, we were the lowest ranked, even though some of my aunts were the same age as my sisters. So my sisters had to do everything. When there was food to cook, they cooked for everyone from age 9, and they were the last to eat. It was also their job to get water.

That was a challenge. We didn’t have fresh water. We had to walk over to the next town, where hopefully they would have water. But then everybody would be fighting. Adults would take water from kids, we’d be hit and scratched. But I knew—if we were sent for water, we’d better come back with water.

But I also spent a lot of time with my grandmother, and that was different. I had been really sick when I was young—I had meningitis. I used to get seizures. I had polio, and that affected my walking. The doctors said I had months to live, but my grandmother believed I would live forever. She was a pastor, and I learned more following her around then I ever did in school. I learned about love, forgiveness, kindness—she was spreading the word of God to everyone, all day every day. We would pray for people who were sick, and when we got home, my grandmother told me I’d saved them from HIV or cancer or whatever it was they had. I never knew that they died a couple of days later—I believed I had so much power. When kids killed each other in the street, fighting over nothing—that happened all the time—on Monday my grandmother would take me to one kid’s funeral, and then the next day we would go to La Victoria and see the other kid in prison. I sat there as she sang and prayed for rapists and murderers, and I learned so much from her.

It was hard. But there was a lot of love.

But for my mom, I guess it wasn’t that easy. She was the oldest of my grandmother’s eleven children, and so she was responsible for her brothers and sisters, for their kids—it was just too much. There were so many of us, and we were literally starving. And my mom…she had my two older sisters, and she could see her life becoming just like everyone else’s there, and she didn’t want that. She didn’t want that for her children.

She said it took her ten years to make the decision to go, until one day she couldn’t take it anymore. She contacted the coyotes, gave them all this money she had saved, and then she started the journey across the Dominican Republic, to where they could get to the water to make the crossing to Puerto Rico. But the journey takes a long time, because you have to move slowly and hide, and on the way it became clear she was pregnant—with me. She’d had a one-night-stand not long before she left. The coyotes could see it.

One night they left her in the woods. They had all been hiding out in the jungle, and when she woke up, everyone was gone. She didn’t know where she was, she had no food or water. She almost died. This couple found her, and they cleaned her up, brought her to a hospital, and brought her back home.

But once I was born, she was determined to try again. When I was four months old, she left again, this time with a machete in hand to make the coyotes finish what she had paid them to do. Once they made it all the way across the country, they got into a yola, a small fishing boat. It can normally fit 6-10 people, but the coyotes cram 30-40 people in there. The Mona Passage between Domincan and Puerto Rico is 80 miles across, and it’s rough water. Those tiny boats aren’t made to handle it. A lot of those people didn’t survive. There was this mother and daughter…the daughter got her period, and people were debating whether to throw her overboard, because the blood would attract the sharks. Mami said that when she woke up the next morning, the girl was gone.

When they got close to Puerto Rico, the coast guard was patrolling, and the coyotes couldn’t take them all the way to shore. They said everybody had to jump and swim, but Mami didn’t know how. She stood there on the boat, and they were yelling at her to jump, but she couldn’t do it. She felt a kick in her back, she fell in, and that was the day she learned how to swim.

She made it to shore at Vieques, a bioluminescent glowing bay, half mud, half water. She hid there from the coast guard, until a fisherman found her and helped her get to La Perla. It’s probably the worst place to live in Puerto Rico, but it was heaven compared to Dominican. People either respect Mami, or they hate her. She has a strong personality—she’s aggressive, but very cool and smooth and funny. And in a new place, where she looked and sounded different, and was trying to blend in, being a boss was an asset. She met someone right away, they got married, and she got pregnant. He was 17, she was 20. His parents didn’t approve of her, but he was good to her, and they lived in a real house, with plenty to eat. But when she gave birth to my sister Danerys, she had terrible postpartum. Nobody understood what it was, and everyone thought Mami had just gone crazy. When the baby was just a couple of months old, my mom’s husband suggested they take a vacation. It would be good for her.

They left the baby with his parents, and drove for five hours. He got out of the car, told Mami, “hang on, I have to check something, wait here,” and then he drove off and left her there.

She was devastated. She turned to drugs—it’s the only time she did drugs. And then once she got out of that, she left Puerto Rico and went to New York. She didn’t understand her rights, she had no idea how to get her baby back, she didn’t know what else to do.

(c) Yanerys

It took my mom 6 years to get her children back. She’d been working that whole time on trying to get a green card for me and my older sisters, and trying to figure out what she could do to get Danerys back. When she knew that Rosemary, Amnerys and I were on our way, she went back to Puerto Rico. She contacted Danerys’ father and asked to see her. He told her, “she doesn’t belong to me.” Danerys had been adopted by his sister and her husband, because they couldn’t have children of their own. They had changed Danerys’ name to Yajaira. Mami begged and begged, asked to take her to the movies or to Burger King or something. And so finally they agreed, and my mom took her and ran. She kidnapped her own daughter and brought her back to New York.

Rosemary, Amnerys and I arrived at almost the same time. When I got my green card, that was the first time I ever signed my name. A woman in line showed me how. And even though we had our green cards, it wasn’t easy. Amnerys was pregnant. She had gotten married the year before—she was only fourteen, but that’s normal there. Immigration wouldn’t give her the green card if they knew, because it would be like two for the price of one. So we hid her pregnancy during the journey—and it wasn’t easy, because she was eight months along. But she was so young and so malnourished that we got away with it.

Mami took us all to the doctor right away. We were iron deficient and Vitamin D deficient and basically starving. The only thing about us that was healthy was our teeth. There was no soda or candy or anything in Dominican. Coconut water was my soda. Sugar cane was my candy. So we had no cavities, and that was something.

Yajaira was much healthier. She had a nice life in Puerto Rico, in a big house with a piano. She was kind of chubby, 85 lbs. But within a couple of months she had dropped down to 40 lbs.

I mean, of course she did. Her family back in Puerto Rico, they never came after her, so I’m sure she felt abandoned by them, after being kidnapped by this woman claiming to be her mother. We were all strangers to her. She refused to eat, refused to shower.

Mami took it personally, and she started hitting Yajaira. That’s how my mom grew up, after all—getting beat up by your mother in my country is love, is respect, is showing you authority. That is how kids are raised. But when you do that to a kid who considers you a stranger, who has never been touched like that before…it just makes them fear you more. Mami was trying to beat the love into Yajaira, and it was never going to work.

After a few months, we sent her back home to Puerto Rico. My mom’s story is still that she was so ungrateful, that she had it the best out of all of us girls, on and on. I went to visit Yajaira a decade later. She had been so traumatized by what happened to her, she would wake up in the night screaming. But Mami never saw it that way.

Of course, life with Mami wasn’t that easy for Rosemary, Amnerys and me, either. I had dreamed for so long of meeting my mother, and the reality…well, it was disappointing. I believe Mami had been damaged by what she had gone through, and after Yajaira left, things got even worse. My mother had a lot of anger in her, and she vented it on me. She believed that if she had been able to leave Dominican that first time, if she hadn’t been pregnant with me, then everything would have been different. She beat me badly, a lot.

Because I was kind of used to that, I looked up to my mom, but I was afraid of her. When you respect someone out of fear, instead of love, your relationship will never be good. Life with Mami was so different from what I had with my grandmother. She was my angel, and I missed her so much.

It was worse for Rosemary. Back in Dominican, she was the strong one, she protected me, but once we got to New York, it became clear how weak she really was. She was 6 years old when Mami left us. I think about it, what if I were to leave my son? He is 6 now. It would destroy him. And now Rosemary is 33 years old, she suffers from depression, takes painkillers and sleeping pills all day long. She never recovered from my mom’s abandonment. It’s like she’s still waiting for her Mami.

I didn’t like America either. Everything is so gray and dark and dirty and cold. I used to be outside all day every day, and now I was stuck in an apartment. I didn’t like the food. I didn’t see myself or people like me in anyone. The worst part—and this is so funny, in a way—was seeing African Americans. They looked Dominican like me, but when I would go up to them and speak to them in Spanish, they couldn’t understand me. That broke me.

When I got here, I didn’t know how to read or write, I couldn’t speak English, I couldn’t tell time, tie my shoelaces, I didn’t know directions, I couldn’t dial a number. Ten years old, and I didn’t even know my colors. That’s just not the kind of stuff I needed to know. But if I knew anything from Dominican, it was how to hustle. And since I was here, I was going to make it work. I fought for myself. I learned to read and write in Spanish, and then I learned English. I was 12 or 13, watching “Barney” like I was a little kid, because the music made it easier to learn the language.

I’m grateful that I grew up with that. Kids that are born here, they have all the opportunities they want, and they drop out. They cut class. I never cut class. If I didn’t know something, I would befriend the teacher, offer to clean the chalkboard or something, so that I could learn. Other kids would pick on me, call me a hick or whatever, and I would go for their heads. I’d been raised to fight.

But I was still so homesick. I would throw up, I missed my grandmother so much. We had to wait every month to call. My grandmother would travel to a town a couple of hours away where somebody had a phone, and then we would call her. She passed from cancer when I was 16. That hurt, so much, but she had been given a terminal diagnosis almost 10 years before. My mom even bought her a coffin. But she held on. Right before she passed, she called me. She was so sick, she couldn’t remember hardly anyone or anything, but she remembered me. She said, “when you were a little girl, you almost died on me. And I gave you to God and I promised God that you belonged to Him. Now you need to promise me that you will one day give yourself to Him. You don’t belong to me, you belong to Him.” I promised.

Not long after that, I met a boy. He spoke English, he was Americanized, he was from Harlem. He had style and swag. We stayed together for 13 years, and we had a child together, my son Kaysen. Then 2 years ago, my mom decided she had to go home to Dominican. Everything she had gone through, fears about ICE—all of it. She didn’t want to deal with it anymore, and she finally felt she had an opportunity to let it all go.

And while I was dealing with that, my boyfriend left me for another woman. He abandoned me just when my Mami was leaving. Until that moment, his love was the only thing I’d been able to rely on. I thought it was the best kind of love, but it wasn’t. I know now that him leaving was good for me. I could finally stand on my own. His parents are there for me and their grandson, and I’m not holding onto anyone’s love.

When Mami decided to go home, it wasn’t worth it, to be so far from her children for so long.. That she should never have left. But then I went home to visit, and it’s so terrible there. Kids getting killed by the cops, people killing each other over something small. Kids killing each other. That is not the life I want.

Now, I have my son. I take care of both of my older sisters’ kids. Coming to America can give you freedom, but it will cost you a lot. It can cost you your mental health, your inner freedom, your inner peace. It is worth it, to eat steak? Or is it better to eat eggs every day?

For me, it worked out. But not for my sisters. So I’m fighting for my nieces and nephew, because it’s not their fault their mothers couldn’t handle what happened. I have that love that my grandmother embedded in me. Things are better. I went to school, to college—I’ve ended up in almost every program NYC has to offer. I’m studying Esthetology at the Aveda Institute. I can think now. I can sleep, I can breathe, I can laugh and eat. I can feel. For so much of my life, I couldn’t tell if I was feeling too much or not feeling at all. Now I feel blessed, and lucky.

I’m alive. I always have a job, I work work work. I will fry my French fries with pride, because they will get me to the burger, will get me to the cashier. I make my tips at restaurants and hair salons. I went to college, but I like working with people, talking with people. I learned from my grandmother not to care where anyone is from or what they’ve done—it’s who they are. Life is so much easier that way.

I’m an American. I’ve been here since I was 10. I’ve earned it. It took so much for me to stay here and stay out of trouble. I’ve never been arrested, I’ve never even gotten a parking ticket. I pay my taxes. Those of us who come here, we’re not really thinking we’re here to live the American Dream. We’re just here to survive.