Regina was born in Israel, but emigrated to the U.S. with her parents when she was one year old. Her parents were proudly American, as they understood it, and Regina was proudly American, as she understood it. The two were very different.

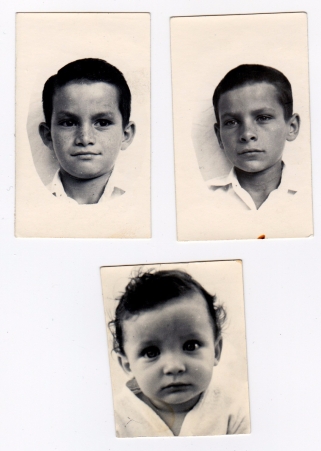

Passport photos of Eddie, Peter & Regina

My parents’ story has to start with the war, as so much of their understanding of the world came from their experiences during WWII. My father Josef and his brother Chaim fled the łapanka (the roundup of Jews in Poland), and ran away to Russia, where they immediately arrested and sent to a Siberian labor camp. The rest of his family perished in the Warsaw ghetto and at Treblinka. The labor camp saved my father’s life. When he was released in 1941, he made his way back to Poland and tried to join the Anders Army—but they wouldn’t take him because he was Jewish. They said to him, “We don’t need soldiers who hide behind corners and shoot with crooked bullets.”

So he joined the Koścuizko First Infantry Division, another Polish force, but with Russian commanders. At that point, the Russians were dying by the millions, so they were happy to take anyone. Josef was trained as a tank commander, and rose to the rank of captain.

Aldona, my mother, did what she had to do to survive the war. She slept with whomever she had to sleep with. When my parents met, their differences didn’t matter as much as they might have, had they met before the war. She was Catholic, he was Jewish…but they fell in love.

Not too long after, my father was handed a letter to sign. It said, essentially, “When I die, I want to be buried as a loyal member of the Communist Party.” His commanding officer ordered him to sign it. Josef explained that, frankly, he was not a good Communist, that he was a Socialist and he believed the Communist Party was corrupt and it was just going to be the same kind of dictatorship all over again, and this is not why he laid down his life for his country, and so on. His commanding officer said, “Look. You can either sign it, or be named an enemy of the people, and that’s not going to end well for you.”

So my parents had to get out of Poland. Josef’s brother Chaim had survived the war, too, miraculously, and was living in Israel, so they went to join him—but also, Israel was the only place that would take them, at the time.

It was very difficult there, because it was a new country. They arrived in 1956, so Israel had only been in existence for less than 10 years at that point. It was largely desert, and there were a lot of Bedouin villages, Arabs, Jews from surrounding countries, and survivors of the Holocaust. Most of the people there were fairly…scarred.

There wasn’t much of an economy. Josef had been trained as a machinist, so he worked as a fix-it guy, repairing bicycles, cars, whatever work he could find. He was okay—as long as he had work to do, my father was always going to be all right. But it was brutal for Aldona. Her health was suffering from poor nutrition, and she had my two young brothers Peter and Eddie to care for. They were so poor, but that wasn’t the hardest thing. There was the stigma of being in a mixed marriage, particularly in a Jewish country, surrounded by so many Holocaust survivors. My blonde, blue-eyed Polish mother, when the Poles were arguably among the worst collaborators during the war, and were generally speaking anti-Semitic…no one would speak to her. There were many people who wouldn’t allow their children to play with my brothers.

Aldona tried, at one point, to go back home to Poland. She went to the consulate, and they told her that she and my brothers could go—but my father could not. He wouldn’t join the Communist Party, and, more importantly, he was Jewish, so he was never going to be welcomed back. My mother surrendered her passport over to the consulate after that.

But they needed to go somewhere. They felt so much shame, going to the store with just enough money to buy a loaf of bread, nothing else, not a piece of penny candy for my brothers. That wasn’t the life they wanted for their children. And now they had three to care for. I was a surprise, since my mother wasn’t supposed to be able to have any more children. She had seven miscarriages in a row after Eddie was born. She was told by the doctors in Israel that she wouldn’t survive the pregnancy…but her mother had died from a botched abortion when Aldona was eleven, and she really just loved children, so she went ahead with it. And there I was.

They applied for visas to a variety of countries, and it was fairly easy this time around, because my father was a skilled laborer. They were given the chance to go to Australia and Canada, but they wanted to go America. A Catholic organization, Caritas, sponsored their trip. They gave them tickets for the boat ride, helped them get an apartment in the Bronx and paid the first month’s rent.

It was a three-week journey, and we rode in steerage. Everyone on the boat was terribly seasick—except Aldona. My mother and I (though I was just a baby) dined with the crew at their table, because she was the only passenger who felt well enough to eat. When we came into New York harbor, it was snowing, and we didn’t have coats or anything, since we were coming from the desert. My brothers had never seen snow, and of course there was the Statue of Liberty. We didn’t have to go through Ellis Island; my father was given his green card on the boat—again, special privileges because he was a skilled laborer.

We arrived in December of 1963—so that would have been one month after Kennedy was shot. My parents idolized Kennedy. There was Kennedy memorabilia all over the apartment when I was growing up. The same with FDR. I mean, the Marshall Plan with its cans of SPAM literally saved my mother from starvation. Americans were heroes to them. And it was understood from the very beginning that we were all on the path to citizenship. The paperwork was already underway when we arrived. That part was all very easy.

What was less easy was finding work. Josef didn’t speak English. But he did speak six other languages, including German, Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, Ukrainian and Polish, so he just went door to door at machine shops in Yonkers and Long Island City until he found someone who spoke one of them, and would hire him. But then the work didn’t pay much, particularly since he was the greenhorn, and also because he was Jewish. He demanded a raise, and when he was told he could have an extra nickel an hour, he was so proud of himself. He had made it in America.

We lived in a one-bedroom apartment, filled with furniture donated by Caritas, though my father paid them back for everything they had done as soon as he could. For about a year, there were actually seven of us in that apartment, as some former neighbors from Israel came to stay with us until they could get on their feet. My brothers went to school, though of course they were starting late, and it wasn’t like there were ESL classes for Hebrew, which is what my brothers spoke and wrote in. They still can’t spell, and their handwriting still looks like they write with their feet. My mother listened to the radio and studied the signs at the supermarket to learn English.

She desperately wanted to move to Greenpoint, where all the Polish people were living. After having been so lonely in Israel, and now being unable to communicate, she just wanted to be with her people. But Josef wouldn’t do it. He said, “Why dide we leave Poland, then? This is where we live.” So we stayed in the Bronx, and we assimilated.

Aldona, Eddie, Peter & Regina on Burnside Ave. in the Bronx

But assimilation meant different things for each of us. My parents were deeply patriotic. They were involved in the community, my mother especially. She was the treasurer of the PTA at the school my brothers and I went to, and eventually went to work as a school aide. She started a clothing exchange at the school after seeing how many kids would arrive without coats or proper shoes. She must have clothed thousands of kids. And they took their civic responsibility very seriously. My mother researched every single candidate, down the most obscure school board elections, and she could never understand why everyone didn’t do this. The first time I voted, we celebrated—this was a big deal, this was Democracy, this was being an American.

My mother and father believed fiercely in the American Dream. They wanted so much for us. Peter and Eddie were never discouraged from going to school—both started college, though they didn’t finish—but my father’s experience had taught him that if you could work with your hands, you could always put food on the table. But that wasn’t an option for me, a girl. So they insisted that I use my brain, get an education, go to college, so that I would never be dependent on a man. This was why they had come to America, so that their children would have choices. So that we would have freedom.

Aldona & Regina

Like my parents, I wanted so desperately to be American—but I accepted and valued the parts of America that my parents didn’t really understand. I didn’t want to be the little immigrant girl, which it was so clear that I was—to everyone except my mother. She would make these hideous granny square concoctions that she would make me wear, or she would dress me like a doll in crinoline underskirts. This was New York in the 60s and 70s—nobody wore that.

My parents would take us to Yankee stadium, delighting in this most American of activities, but they would bring a loaf of rye bread, grapes and a glass jug of water. No hot dogs and sodas for us, and I would be so embarrassed, because everyone in the bleachers would know that we weren’t American. I wasn’t allowed peanut butter & jelly sandwiches for lunch, but a container of beet salad and a hard-boiled egg. My parents, having nearly starved to death, couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t want to eat their good food. I wanted to dress like the girls I went to school with in Riverdale, the fancy part of the Bronx, but even if my parents had the money, they would never have agreed to that. Clothing that wasn’t strictly utilitarian was just bizarre to them. They believed in buying only what you need—which isn’t exactly the American way.

Things got a lot worse when I became a teenager. My mother had no idea what to do with me, and the more they tried to protect me, the more I wanted to prove I was a badass, a real American. When I came home with a tattoo, they told me, “The only women who get tattoos are criminals or prostitutes. Which one are you?” I said, “I can’t be both?” I’m lucky I didn’t get my teeth knocked out.

“I would give anything to have one more day with my mother,” Aldona would say one day. “You miserable ungrateful girl, all the things we sacrificed…” she would say the next.

And when I wanted to go to concerts, to stay out late in Manhattan, my parents were terrified for me. They saw so much rape and abuse of women in the war. My mother experienced some of that personally. That was, frankly, her understanding of sex, even within the loving marriage she had. She would talk to me about rape, but not about normal bodily functions and desires. Those were shameful. And once I got over that shame, their attitude made me push at those boundaries even further.

It all worked out. I didn’t get pregnant. And now that I have perspective, I can see that they weren’t wrong. I can see that, more than anything, they were afraid that I was throwing away all the opportunities they had fought so hard for me to have. But I went to college, and I am not dependent on any man for my income. I have what they wanted for me.

I still struggle within myself to feel completely American, though. My children will never forgive me for not teaching them Polish when they were young, but I honestly didn’t see the point. And sometimes I catch myself feeling like a fraud, like an inferior American. I was attracted to my ex-husband’s family because they were quintessentially American. They were members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and they lived in this giant house in the suburbs. My family was messy and we yelled and screamed and that was normal. But my in-laws’ house was perfect, like a Currier & Ives mirror world. They owned a boat. They skied. They vacationed in exotic places. They played the piano.

Growing up, I desperately wanted to play piano. We had one that we got for free, and I taught myself and I got pretty good, so good that a concert pianist neighbor offered to teach me for free. But my parents said no, because what was I doing to do, become a concert pianist? What was the point?

There was no point to anything that was impractical, that was wasteful—and the arts, while culturally important, were wasteful for young children trying to make it in a new country.

With my own children, I’ve overcompensated. Anything creative they wanted to do, I was for it. Now my kids are actively pursuing careers in the arts, and I’m so proud. I don’t know what Josef and Aldona would think, though. They never understood what I do for a living. I’m a publicist in the music industry, and I would show them an article about one of my artists, and I would say, “Look, I did that.” “You wrote the article? You made the music?” No…I just made it happen.

My parents could never completely understand America. My father died never having had a credit card, never wanting to get a loan so he could buy a house. He lived the last years of his life on a couple of hundred dollars a month, but he would shove hundred dollar bills in my children’s pockets for their birthdays or on holidays. He had a few hundred thousand dollars saved in his bank account, intended for his grandchildren’s college fund, even though my brothers and I were all earning good money and perfectly capable of taking care of our children.

The idea that immigrants are looking for a free ride is a fallacy. My father would never turn his nose up at a job. He had no false pride. Whatever work he could do, whatever would put food on the table, he would do it. No job was beneath him. And tied in with that was a certain…not disrespect, but a lack of understanding of white collar jobs, and so not as much respect, as for work that my parents understood. As such, they were unfailingly generous tippers, and unfailingly polite to people in the service industry. And when new immigrants rolled into the neighborhood—Mexicans coming in, Albanians coming in, Koreans coming in—my father would say, “they are such hard-working people.” It was the highest compliment he could give.

What a story! It brought tears to my eyes.